One summer I travelled to villages of India documenting vernacular architecture. My interest in vernacular architecture of India was spurred by the fact that it is vanishing fast. People prefer to build in brick and cement more now, for obvious reasons.

A large part of my writing is based on observations and conversations with the villagers. My aim was to underpin patterns of building in the region.

Design and Construction

One very interesting characteristic of this architecture is- how they scale their spaces. Construction, here, happens without yardstick and drawings. Design is decided as people talk amongst themselves. The dimensions of the structure are decided with the help of their own body. The measurement unit is one hand which is almost equal to one and a half feet. The rural people of India consider one hand as the distance between wrists and elbow only. The spaces are usually in multiple of one hand. In fact, hand is used for deciding almost every measurement in the building- from foundations to thickness of the walls and roof. For instance, the foundation of a house in Phulgoan village of North India goes up to 6 feet (4 hands), width of the wall 3 feet (2 hands), and height of wall 9 feet (6 hands) and so on. The locals undertake multiple responsibilities of visualizing, designing, material procuring, and building. It is an all together different approach to design and construction where design decisions are limited to talks between the family members. Surprisingly, a few even allocate function to the spaces only after they are built.

A House in Chattisgarh State

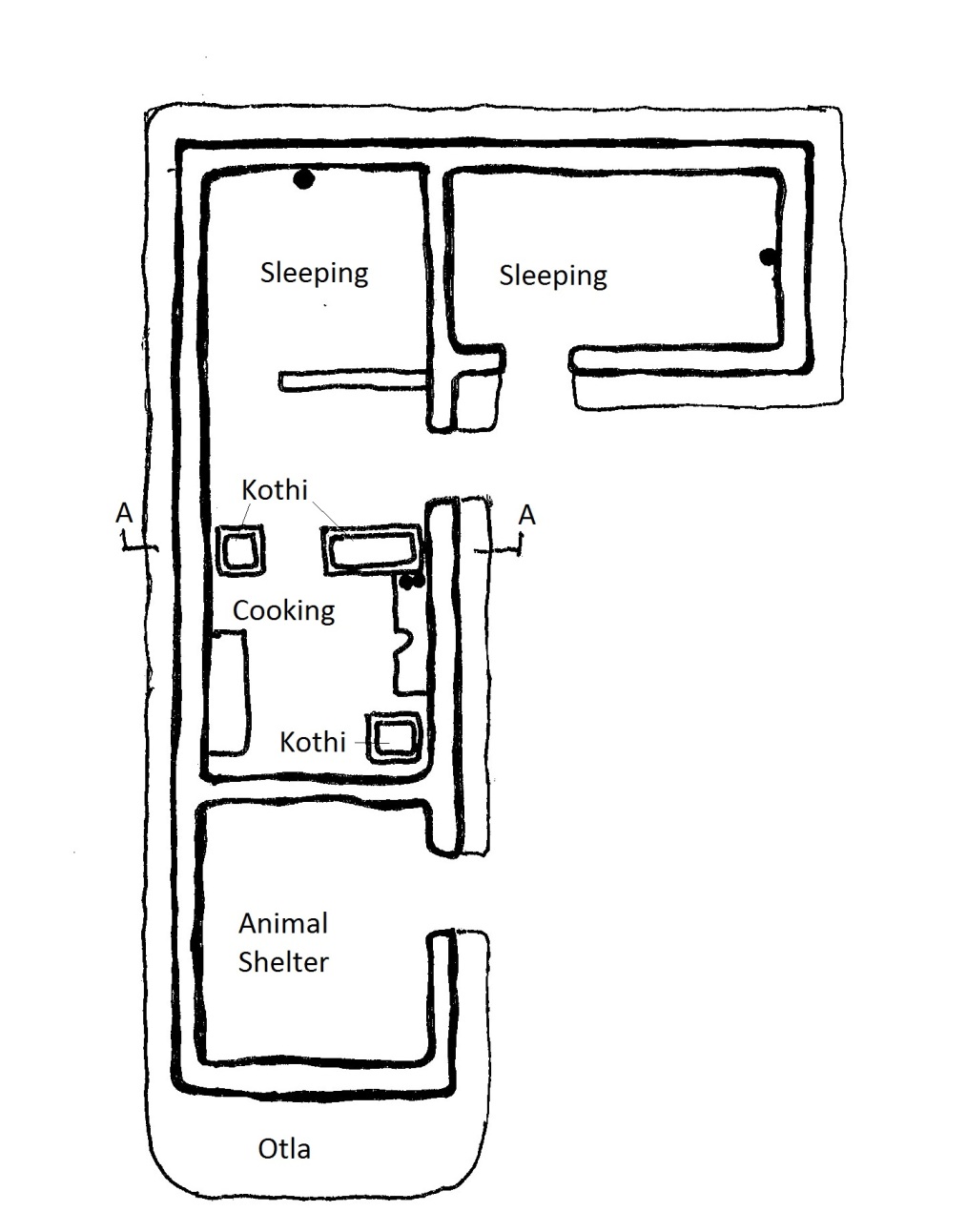

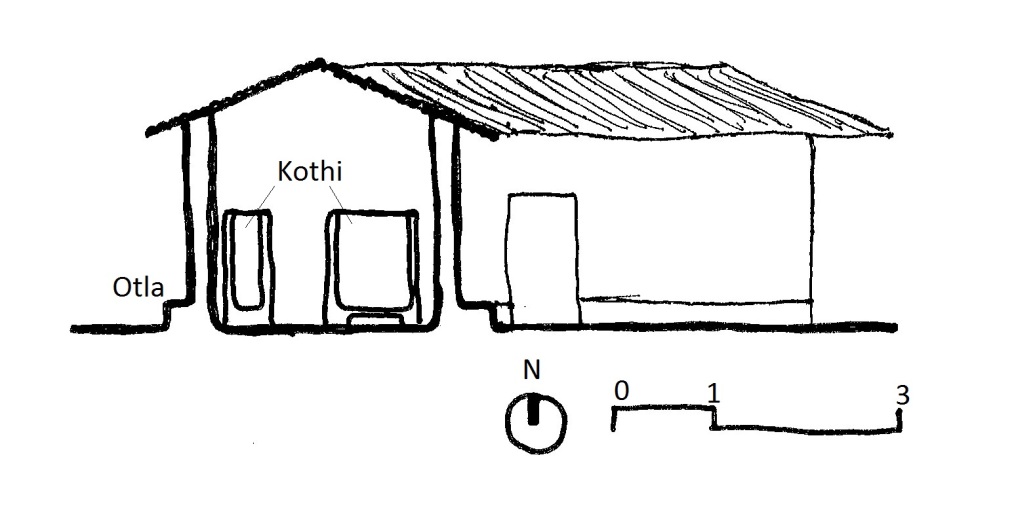

The houses in each region of India follow some underlying patterns. The custom of building linearly prevails in chattishgarh state. As the need arises, new spaces are added eventually forming a central courtyard. All the houses of Chattishgarh region have a few common elements- like the otla, kothi (granary).

Otla

Unlike the urban houses where privacy is the prime consideration of design, the rural India gladly bring a part of their private life at the edge and let it blend with their social life. It is not uncommon to find people interacting, children playing, women cutting vegetables at otla. The otla is a platform outside the house. It is essentially present in every house only in different scales. Sometimes, the goes up to 2.1 meter that a person can easily sleep in the space, sometimes it is as little as 0.3 meter- a space meant for sitting only. What dictates this design is not known.

Kothi

Another element commonly found in chattishgarhi houses are Kothi. Kothi is a granary which is designed with suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents and insects. These are always detached from the external walls to avoid moisture penetration. A granary also acts as an element to divide the space. Depending on its placement, a granary separates the storage area from the living area, or cooking area from the living area. Small vents are also noticed in the area below the granary to perhaps to supply oxygen to the cooking area.

Windows are practically absent in the chattishgarhi rural houses. The prime reason of this lies in the climate of the region. Where temperature goes as high as 45˚ C in summers, it is advantageous to have thick walls without windows. Ventilation happens through the perforated roof and also the gap between the roof and the wall. In the absence of window, kitchen filled with smoke from burning wooden fuel is hardly a sight here.

Though this practice of building one’s own shelter in the rural India continued for a long time, now it is rapidly replaced by pakka makan (brick and cement construction). One of the prime reasons for choosing pakka makan over kaccha (mud houses) is pakka makan is a status symbol. Other reasons are maintenance, cost and lack of skilled labour. Desire to have permanent structure, symbolises stability. Due to lack of awareness, we might witness the death of this art.